This guide is for all beginners who are interested in learning more about the technical details of their favourite consoles and games. The guide aims to be as console-agnostic as possible, but after you have completed this you should look into the details of the specific console you are interested in.

Many people are confused about what exactly is involved in reverse engineering or why exactly people would “waste their time” on such a task. Well, let’s find out…

Presumably by being on this page you at least have a slight idea about what reverse engineering is and may even have some pre-conceptions.

At the end of the day it really is what it says on the tin, “Reverse engineering” taking the engineering process in reverse from finished product to learn how it was made.

A reverse engineer is a scientist that studies man-made object rather than natural phenomena.

OK, but why exactly would people spend their time reverse engineering an old game instead of creating brand new games?

There are many reasons for this such as pure nostalgia and preservation of a part of our modern history, the same way people study traditional art, studying games is a rather obscure version of appreciating human history.

When a game is reverse engineered it becomes open to new life, new levels, sounds and more hours of fun. Reversing is like a game inside the game, when you have finished playing the game the fun of reversing can begin!

It is almost guaranteed to make you a better programmer, you are studying the code of very intelligent developers and you can learn from both their genius and their mistakes.

Not only that but you will start to understand in depth how computers work and it can help protect your own games from hackers and may even start you on a path learning about cyber security and malware protection.

Consider this: There are many devices that you use daily, like physical gadgets or computer programs, but most people don’t have the skill to look inside them to check if they might invade your privacy or have flaws that could make you less safe. Reverse engineering gives you the skill to be able to check for security flaws and tracking functionality that companies often don’t disclose to the public.

The most obvious benefit is to allow people to get more from their games, enjoy more hours in their favourite games, get that nostalgic buzz!

Whether that is translating a game into a new language, improving the sound or visuals, or porting a classic game to a more modern system, you are bringing the enjoyment that this game gave to you to brand new audiences.

It might not exactly be saving lives in the traditional sense, but the hours of joy you can bring to gamers old and new is priceless.

Yes, in fact there are many cases where the courts have sided with the reverse-engineer when it comes to anti-competitive practices.

If you are interested there are a few court battles that are relevant:

In fact, reverse engineering already plays a vital role in ensuring your freedom in an increasingly more technological society. How do you know a voting machine is accurately counting your vote? Or how do you know if your computer is spying on you? You could reverse engineer it and find out.

Presumably if you have read this far you are interested in learning at least the basics of reverse engineering, how exciting! Trust me you will absolutely love it when you get started and in fact it can be a little addictive…

Let’s start at the beginning, you might have seen ROM files before, well actually I can safely assume you HAVE used a few of them in your favourite emulator.

But what exactly are ROM files? How did that big plastic cartridge become a single file that can be run into an emulator? Let’s find out!

ISO files are sometimes incorrectly called ROMs and technically they are a copy of data that was on a Read-only memory format but there are some fundamental differences between them.

If you are unaware ISO files are copies of the data on a CD, DVD or Blu-ray Disc. Thus one of the major differences between this and a ROM file is it actually is a standard file format that can be opened in a tool such as Windows Explorer or Apple Finder and you can explore all the subfiles inside.

It is generally easier to find graphics, sounds, maps, videos and such in ISO files as they tend to be individual files with a useful file extension. Although this is not always the case as many games engines like to pack up all their files into a single or multiple compressed files.

As we have said before games are just a series of 1’s and 0’s so we could look at your favourite ROM or favourite ISO file in this way and you could, with enough time, find out what each bit represents.

However, humans are not very good at distinguishing parents of bits, so we have a much easier way to view these files in a format called Hexadecimal! In Hexadecimal every single Byte in a ROM or well any file on a computer can be represented as 2 digits using the numbers 0->9 and the letters A->F.

Don’t worry you will not need to learn how to convert to Hexadecimal, there are plenty of tools for that, and you will pick up the most common Hex codes as you go along.

In fact you may have already seen Hexadecimal if you have worked with Colours as they can be represented as 3 different bytes (Red/Green/Blue), each one of those bytes can be represented as 2 hex digits for example #FFFFFF (White).

Now that you know why the Hexadecimal notation is useful for developers to represent bytes, let’s use a tool that every reverse engineer has handy at all times, the HEX editor!

As we know a game is build up of either a single file (ROM) or multiple files, but at the end of the day they are all files and all contain bytes of data.

So we know know that we can represent each byte as two Hexadecimal digits, why don’t we open up some of those game files!

Depending on your platform there are multiple good HEX editors to choose from, but here are just a few:

Some ROM hacks are done purely with a HEX editor and emulator so this is a powerful tool to get you started, but there are many other useful tools to learn along the way to make it even easier.

So go on give it a try, open your favourite ROM in a Hex editor and see what you can find!

Files come in many different formats, for example an image format such as JPG is very different in structure from an executable file such as a Windows Executable. Files tend to have an extension such as .jpg or .exe but this does not always match what is actually contained inside the file.

There are so many file formats out there (and many variations) that you couldn’t possibly know them all, so its best to just learn what you need when you need it. Most standard formats are well documented online and for the others that may be custom to a specific game or application we can reverse engineer the assembly code of how the software reads (or writes to) the file.

Now you know the basics of how data can be represented you can dive into many different file formats used in games. You can view them in Hexadecimal with a Hex Editor and you can spot the Magic Header (if the file has one). This can be very useful for looking at files in ISO files, especially if they do not have a file extension.

The Magic Header for a file tends to be the first few bytes of the file, for example WAV sound files start with the first 4 ASCII characters WAVE.

Wikipedia has a useful table of the most common file formats and what their Magic headers are: List of file signatures - Wikipedia

So you could open your file in a Hex editor and search that page for what file type it is. But there exists an even easier solution, systems based on UNIX come pre-installed with a useful tool called file which can tell you what a file contains regardless of its extension.

An example of using file:

file ./folder/unknownfile.dat

Many files used in games could be a custom format created specifically for that game (or engine), understanding how to decode these custom file formats is a vital skill that is worth learning.

We will cover how to reverse engineer a custom file format in a later lesson, but for now you might be surprised how many games contain standard well-documented file formats on their CD’s or Floppies.

When looking at custom file formats or even just executables, one of the most valuable pieces of data in these files are Text Strings, especially if they are in standard ASCII or UTF-8 format.

There is a really easy way to dump out all the ASCII strings in a file using the strings command like so:

strings your_file_name

A core part of all video games is the Audio, whether as background music or sound effects, finding out how the sound system works for your chosen game can be fascinating. We have a separate post covering Game Audio and Music reversing and file format information.

Instead of relying on an infinite number of random attempts to find hidden codes or features, memory dumps provide an efficient way to access and analyze software. It allows for systematic reverse engineering (RE) of the software to uncover “secret” codes that may only be available in memory.

Knowing how data is structured in memory is a crucial skill to be able to tear apart how software works and ultimately learn about any hidden functionality, security issues or privacy violations.

A practical example is the Nokia 5210 cell phone’s security code. While the manufacturer claimed it was unbreakable, memory dumps revealed a secret sequence (*3001#12345#) to unlock the phone. This discovery can be beneficial to end users who want to unlock their phone or even just for users to know that its possible.

The exact representation a game uses will vary based on the compiler used, system its developed for and even programmer preference.

Here are the most common data representations:

Endianness refers to the byte order or how multi-byte data is stored in memory. It’s important to understand endianness because games often need to work with data structures that span multiple bytes, such as integers or color values.

There are two main types of endianness:

If you’re developing a game on a little-endian PC but targeting a big-endian games console, you’d need to swap the bytes when loading or saving data. This byte-swapping can be essential when working with things like color values, sound samples, or binary file formats that need to be read and written correctly.

Additionally, some retro consoles, like the Sega Genesis, used a mixture of big-endian and little-endian data formats, adding another layer of complexity. Understanding the specific endianness of the target console and adapting your code accordingly is crucial for retro game development to ensure that data is interpreted correctly, graphics are displayed accurately, and sound is played as intended.

When inspecting a game’s memory it is important to know that the address where the data is stored will change from run to run. So for example if you know the lives is stored at a particular address in memory, if you restart the game you may find that it is stored in a completely different location. So how does the computer know where to look for the lives memory? The answer is simply using pointers.

Pointers are simply variables that point to a specific memory address asnd they can be modified at runtime.

This section will start to look into reverse engineering the actual code that makes the games run on the CPU.

The Youtuber Bisqwit has created an excellent video on how executables work:

Executable file formats are specific data structures used by operating systems to understand how to load and execute a program. These formats vary depending on the operating system and architecture, but the most common ones are:

Note that most executables don’t have any file extension on Unix/macOS and many games consoles. Many games consoles use a modified version of ELF such as the Sony PSP’s EBOOT.bin files or even completely custom implementations like the original PlayStation’s PS-EXE format.

An Application Programming Interface (API) is a collection of functions that are so common that they are provided to every programmer of a certain platform (e.g. PS1, Xbox 360, Windows). These functions can either by included in the executable directly or dynamically linked to at runtime from a common set of libraries.

API functions are very useful when reversing a game or application as they tend to have documentation associated with them and give hints as to what the code that calls them might be wanting to do. So they are a very good place to start when reverse engineering an executable.

APIs are typically distributed in several ways to allow developers to integrate them into their applications:

A static library is a collection of precompiled code that is linked directly into a program during the build process. This means the code from the library becomes part of the final executable, allowing the program to run independently without needing the library files at runtime. Static libraries typically have file extensions like .lib on Windows and .a on Unix-like systems.

A dynamic library is a file containing code and data that can be used by multiple programs simultaneously. Instead of including the code directly in each program, they load the library at runtime, saving memory and allowing updates without recompiling the programs. In Windows, these are called DLLs (Dynamic Link Libraries), while in Unix-like systems, they are often called shared objects (.so files).

Here’s a table of Microsoft Visual C++ (MSVC) versions and their associated runtime DLLs that can be imported. This table provides a quick reference for understanding which runtime DLLs correspond to different versions of MSVC.

| MSVC Version | Runtime DLLs | DLL File Names |

|---|---|---|

| MSVC 6.0 | Visual C++ 6.0 runtime | MSVCRT.dll |

| MSVC 7.0 | Visual Studio .NET 2002 (VC7) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP60.dll |

| MSVC 7.1 | Visual Studio .NET 2003 (VC7.1) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP71.dll |

| MSVC 8.0 | Visual Studio 2005 (VC8) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP80.dll, MSVCR80.dll |

| MSVC 9.0 | Visual Studio 2008 (VC9) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP90.dll, MSVCR90.dll |

| MSVC 10.0 | Visual Studio 2010 (VC10) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP100.dll, MSVCR100.dll |

| MSVC 11.0 | Visual Studio 2012 (VC11) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP110.dll, MSVCR110.dll |

| MSVC 12.0 | Visual Studio 2013 (VC12) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP120.dll, MSVCR120.dll |

| MSVC 14.0 | Visual Studio 2015 (VC14) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP140.dll, MSVCR140.dll |

| MSVC 14.1 | Visual Studio 2017 (VC14.1) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP140.dll, MSVCR140.dll |

| MSVC 14.2 | Visual Studio 2019 (VC14.2) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP140.dll, MSVCR140.dll |

| MSVC 15.0 | Visual Studio 2022 (VC15) | MSVCRT.dll, MSVCP140.dll, MSVCR140.dll |

Notes:

xx denotes the version (e.g., 80 for Visual Studio 2005).MSVCPxx.dll.Here’s a table summarizing the tools for viewing the insides of executables and libraries:

| Tool | Platform | Description | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| objdump | Linux, Unix, macOS, Windows | Disassembles and displays information about object files and executables. | objdump -d <file> for disassembly, objdump -t <file> for symbols. |

| readelf | Linux, Unix | Displays detailed information about ELF files, including headers and segments. | readelf -h <file> for headers, readelf -s <file> for symbols. |

| nm | Linux, Unix, macOS, Windows | Lists symbols from object files, executables, and libraries. | nm <file>. |

| gdb | Linux, Unix, macOS, Windows | Debugger that can also inspect executable contents, disassemble code, and view symbols. | gdb <file>, then use commands like info functions or disassemble. |

| Ghidra | Windows, Linux, macOS | Free and open source disassembler and debugger with interactive analysis capabilities. | Load the executable into Ghidra and use the GUI for exploration. |

| IDA Pro | Windows, Linux, macOS | Commercial disassembler and debugger with interactive analysis capabilities. | Load the executable into IDA Pro and use the GUI for exploration. |

| Hex-Rays Decompiler | Windows, Linux, macOS | Converts disassembled code back to C-like pseudo code; an add-on for IDA Pro. | Integrated within IDA Pro; select a function and decompile. |

| Binary Ninja | Windows, Linux, macOS | Modern binary analysis tool with disassembly, decompilation, and scripting. | Load the binary and use the GUI or API for analysis. |

| Radare2 | Windows, Linux, macOS | Open-source framework for reverse engineering, including disassembly and debugging. | r2 <file>, then use commands like pdf to disassemble functions. |

| PE Explorer | Windows | Commercial tool for inspecting and editing Windows PE files. | Open the executable in PE Explorer and navigate through sections. |

| CFF Explorer | Windows | Free tool for analyzing and editing PE files, with detailed views of file structure. | Open the PE file in CFF Explorer and explore different sections. |

| Dependency Walker | Windows | Analyzes dependencies of Windows executables and DLLs, showing imported/exported functions. | Load the executable or DLL in Dependency Walker and explore dependencies. |

| dumpbin | Windows (Visual Studio) | Command-line tool for inspecting PE files, showing headers, symbols, imports, and more. | dumpbin /all <file> to view all available information. |

| MachOView | macOS | Tool for viewing the structure of Mach-O binaries, native to macOS executables. | Open the Mach-O binary in MachOView and browse its segments and sections. |

When decompiling it can be incredible useful to know the exact version of the compiler and linker toolchain was used to build an executable so that the correct decompilation settings can be applied.

The best tool to detect which compiler and linker was used is Detect It Easy (DIE), it is open source and has pre-build binaries available for Win/Mac and linux: Detect-It-Easy: Program for determining types of files for Windows, Linux and MacOS.

Assembly language is a low-level programming language that’s a step above the binary machine language that computers understand. It uses human-readable mnemonics and symbols to represent the basic operations a computer’s Central Processing Unit (CPU) can perform, like adding numbers, moving data, and making decisions.

In essence, assembly language is a way for humans to communicate with computers in a more understandable way, making it easier to write software that can perform specific tasks or functions on a computer’s hardware.

You do not need to learn assembly language to reverse engineer retro games, however, if you want to write your own games from scratch then it is recommended. For reversing you might be dealing with multiple CPUs on a single console so learning the entire instruction set would be too time consuming and by the time you get to actually reversing you may have forgotten much of what you have just learned.

The best way is to learn as you go and use the Internet as a reference when you need to know what an instruction does.

However there are a few basics that you should know before getting your hands dirty and these apply to the Assembly language used in most retro video game consoles. These will be covered in the next few sections.

It depends on the platform (specifically CPU) that your game was built for, here are some examples:

Note that the above are the rough groups, some specific CPUs have more specialised instructions that are exclusive to that console, but mostly its the same programming language.

Here is a simple comparison table that highlights some key differences between different CPU Instruction Set Architectures (ISA). Please note that this table is not exhaustive and focuses on high-level distinctions:

| ISA | Example Instructions | Number of Registers | Memory Addressing Modes | Complex Instructions | Endianness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z80 | ADD, SUB, MOV | 8 General Purpose | Immediate, Direct, Indexed, Register Indirect | Conditional Jumps, Bit Manipulation | Little-Endian |

| 6502 | ADC, LDA, STA | 3 General Purpose | Zero Page, Absolute, Indexed, Indirect | None | Little-Endian |

| 68K | ADD, SUB, MOVE | 16 General Purpose | Register Direct, Immediate, Memory Indirect | Multiply, Divide, Bit Manipulation | Big-Endian |

| MIPS | ADD, SUB, LW | 32 General Purpose | Immediate, Register Direct, Base + Offset | Load/Store, Multiply, Divide | Big-Endian |

| x86 | ADD, SUB, MOV | 8 General Purpose | Register Direct, Immediate, Memory Indirect | Complex Arithmetic, SIMD | Little-Endian |

| ARM | ADD, SUB, LDR | 16 General Purpose | Immediate, Register Direct, Base + Offset | SIMD, Multiply, Divide | Little-Endian |

| SuperH | ADD, SUB, MOV | 16 General Purpose | Immediate, Register Direct, Memory Indirect | Multiply, Divide, Bit Manipulation | Little-Endian |

| PowerPC | ADD, SUB, LWZ | 32 General Purpose | Immediate, Register Direct, Base + Offset | SIMD, Multiply, Divide | Big-Endian |

This table provides a broad overview of these architectures, but there are many more details and specific instructions within each ISA. The number of registers, addressing modes, and the availability of complex instructions can significantly vary even within a single architecture, and the choice of endianness (byte order) can have important implications for software compatibility. For a deep dive into any of these ISAs, you would typically need to consult the official documentation or specific resources for each architecture.

The process of taking a final game executable/ROM and converting it into human readable Assembly language is called disassembling.

You need to choose a Disassembler that works for your game’s Instruction Set Architecture (ISA), this will depend on which console or PC your game is compiled for.

We have a separate post covering how disassemblers work below:

When learning reverse engineering and assembly language programming it is vital to know how a CPU actually works, what are the major parts and how they interact, that is what this section will focus on.

Microprocessors provided a cost-effective way to access computing power. Before microprocessors, developing custom hardware for each game or gaming system was expensive and time-consuming. Microprocessors allowed for standardized, affordable, and flexible computing platforms.

Microprocessors brought a level of standardization to the gaming industry. Instead of needing custom hardware for each game or console, developers could create games for a common microprocessor architecture (e.g. x86, ARM, or MIPS). This made it easier for developers to create games and for consumers to adopt new gaming systems.

LiveOverflow has an excellent introduction video to how a CPU works and what exactly assembly language is.

A CPU for a game console or PC works by following a series of steps to process instructions and manage the game’s activities.

This is known as the Fetch-Decode-Execute-Repeat cycle and it continues indefinitely until the CPU looses power.

Here’s a simple explanation:

An instruction is a basic operation or command that the CPU can execute. These instructions are written in a machine-readable form, usually in binary code, and are the fundamental building blocks of a computer program. Each CPU has its own specific set of instructions, known as its instruction set architecture (ISA).

Instructions can perform various tasks, such as:

CPU instructions are executed sequentially, one after the other, according to the program’s logic. The order and combination of these instructions determine the behavior of a computer program.

In the world of assembly language programming, every Central Processing Unit (CPU) includes an instruction that accomplishes precisely nothing. These unassuming instructions are commonly referred to as ‘No Operation’ or NOPs. When a NOP is executed, the CPU undergoes a brief, yet essential, period of inactivity, ultimately ending up in the exact state it occupied before executing the instruction.

While this might seem counterproductive, NOPs have their indispensable uses. One of their primary functions is to ‘waste time’ intentionally. CPUs operate relentlessly, executing instructions in rapid succession, and sometimes, you need the CPU to pause briefly, awaiting the readiness of another part of the system. In such cases, NOPs prove invaluable. They serve as a placeholder or a delay mechanism, ensuring that the CPU remains occupied without altering its state.

Imagine a scenario where a CPU needs to synchronize with external hardware that operates at a different speed. By inserting NOPs strategically, you can create the necessary time gaps, allowing the CPU to align its actions with the external hardware’s pace. This is just one example of how NOPs find practical application in assembly programming, despite their seemingly ‘do-nothing’ nature.

Also NOP instructions can be used to insert empty space or “padding” in the code. This can be useful for aligning instructions in memory or adjusting the size of loops and branches. For example, if you want to ensure that a certain block of code is located at a specific memory address, you can insert NOP instructions to fill the gap between the end of the previous code and the desired location.

You can think of CPU Registers as small (64-bit/32-bit/16-bit) global variables that the CPU accesses directly.

Each CPU has a number of built in registers which can each store a set number of Bytes, the number of bytes that they store is defined by the CPU, for example a 64-bit CPU will have 64-bits for each register.

Almost all CPUs have special registers that are designated for a particular purpose, one common example is the Program Counter which basically stores the location of the next instruction to execute on the CPU.

But what happens when you want to store more data than the limited number of registers available on the CPU? This is where the computers RAM comes in, no matter how simple your console or PC is it will have some sort of RAM available and is used to store data such as the players X and Y Position.

So how do we read and write data to this RAM? One simple way of saving and loading data is with something called the Stack.

You can think of the stack like a deck of cards, you can add new cards only to the top of the deck which represents writing to the stack. For reading data from the stack you can only take the top most card, which is also the most recently written piece of data.

Although unlike a deck of cards when you add more data the address of the data goes downwards instead of upwards, so if the first element in a stack is at position 10 then when you add another byte of data its address would be 9.

The stack grows backwards (from high to low memory addresses) to efficiently separate it from the heap, which grows in the opposite direction. This allows both to expand without quickly running into each other, making better use of available memory.

The CPU has designated instructions to read and write from the stack, often called push and pop. Where push adds an additional piece of data to the stack and pop removes the most recently added data from the stack of data.

When you need to store more data than the stack can handle or require memory that persists longer than a single function call, the heap comes into play. The heap is another part of your computer’s RAM, used for dynamic memory allocation, such as storing large objects, game assets, or variables that need to exist throughout the program’s execution.

You can think of the heap as a large pool of memory where you can request chunks of memory as needed. Unlike the stack, memory in the heap can be allocated and freed in any order, making it flexible but also more complex to manage.

Early video game consoles typically did not have a heap due to their limited memory and lack of an operating system to manage dynamic memory allocation. However, as consoles evolved and gained more memory and complexity, the concept of a heap started to become relevant.

Some heaps were handled by the operating system (Xbox onwards) and others were handled by the game engines themselves (PS2, GameCube).

The heap grows upwards, from lower to higher memory addresses. When you request more memory (for example, creating a new object or allocating an array), the heap expands towards higher addresses. This is in contrast to the stack, which grows downwards, ensuring that both areas can grow without quickly overlapping.

The heap is essential for managing memory in programs where the amount of data isn’t known ahead of time or varies during execution. It’s particularly useful in situations where you need to allocate large blocks of memory that might need to exist for the lifetime of the program or until explicitly freed.

Most programming languages provide functions or operators to allocate and free memory on the heap. In languages like C, malloc() and free() are used, while in higher-level languages like Python or Java, memory management on the heap is handled automatically through built-in mechanisms.

This allows you to dynamically allocate space when needed and release it when it’s no longer required, making the heap a powerful tool for managing memory in complex programs.

Interacting with the heap in assembly language typically involves system calls or interrupts to request memory from the operating system. Unlike the stack, which is managed directly by the CPU with specific instructions, the heap requires explicit requests for memory allocation and deallocation.

Instead of passing large arrays or structures to functions (which is slow), you can pass their address. This is faster and allows the function to modify the original data without needing to return the whole structure. That address when saved into a variable is called a pointer, as it points to data.

Function calling conventions are rules that define how functions receive parameters, return results, and manage memory during a call.

Conventions specify whether function arguments are passed in registers (fast) or on the stack (slower) and decide which registers are used for passing parameters. Often, a special register (like eax in x86 architecture) is used to hold the return value.

Conventions also decide who is responsible for cleaning up the stack after the function call either the caller of the function or the callee.

cdecl (short for “C Declaration”) is a calling convention used in C and C++ programming that specifies:

eax register.stdcall is a calling convention used in Windows programming that specifies:

eax register.fastcall is a calling convention designed to improve the performance of function calls by reducing the overhead associated with passing arguments and handling stack operations.

thiscall is a calling convention used primarily for C++ member functions. It is designed to handle the specific needs of methods that operate on objects (i.e. functions that are part of a class).

Disassemblers often rely on function prologues and epilogues as key indicators for identifying the boundaries of functions within a binary. These patterns help the disassembler understand where functions start and end, allowing it to organize the disassembled code into coherent blocks. These tend to be fairly standard as they are created by the compiler.

The prologue is the sequence of instructions at the beginning of a function that prepares the stack and registers for the function’s execution. It typically includes saving the return address, preserving the base pointer (if used), and allocating space on the stack for local variables.

Example (x86 Architecture):

push ebp ; Save the old base pointer

mov ebp, esp ; Set up the new base pointer

sub esp, 0x10 ; Allocate 16 bytes of stack space for local variables

The epilogue is the sequence of instructions at the end of a function that cleans up the stack and restores the saved registers. It usually includes restoring the base pointer and the stack pointer, and then returning control to the caller.

Example (x86 Architecture):

mov esp, ebp ; Restore the stack pointer

pop ebp ; Restore the base pointer

ret ; Return to the caller

System calls are functions provided by the operating system that allow programs to interact with hardware and system resources, like reading files, creating processes, or communicating over networks. They act as a bridge between user-level applications and the core functions of the operating system.

Here are simple examples of making a system call in assembly on Windows, Linux, and macOS.

In Windows, system calls can be made directly using two different methods depending on which version of windows:

int 0x2e: This interrupt vector was historically used to invoke system calls by placing the syscall number in eax and issuing the interrupt. This method is deprecated and replaced by SYSENTER.SYSENTER: This instruction is optimized for making system calls on modern x86 processors. Windows sets up the MSRs (Model-Specific Registers) required for SYSENTER during boot, so user-mode applications don’t need to manage them. However, this approach is not documented for use in applications and is generally intended for internal OS use.Directly invoking system calls using int 0x2e or SYSENTER is highly discouraged in normal application development due to the risk of instability and compatibility issues across different Windows versions. Instead, using the Windows API (like ExitProcess) is the recommended and supported approach.

int 0x2e (pre-Windows XP)The int 0x2e interrupt was used in older versions of Windows (pre-Windows XP) to invoke system calls directly. Here’s an example:

section .data

; No data needed for this simple example

section .text

global _start

_start:

; System call: NtTerminateProcess (similar to ExitProcess)

; System call number: 0x29 (varies by Windows version)

; Parameters:

; - eax: system call number

; - ebx: handle to process (0 for current process)

; - ecx: exit code (0 for success)

mov eax, 0x29 ; system call number for NtTerminateProcess

xor ebx, ebx ; current process

xor ecx, ecx ; exit code 0

int 0x2e ; invoke system call

SYSENTER is a fast system call instruction introduced with Intel’s Pentium II processors and is used internally by Windows for system calls on newer systems. This approach requires setting up specific registers before the SYSENTER instruction is executed:

section .data

; No data needed for this simple example

section .text

global _start

_start:

; System call: NtTerminateProcess (similar to ExitProcess)

; System call number: 0x29 (varies by Windows version)

; Parameters:

; - eax: system call number

; - edx: address of the system call table (set by the OS, usually in kernel mode)

; - ebx: handle to process (0 for current process)

; - ecx: exit code (0 for success)

mov eax, 0x29 ; system call number for NtTerminateProcess

xor ebx, ebx ; current process

xor ecx, ecx ; exit code 0

mov edx, esp ; load stack pointer into edx (just for demonstration)

sysenter ; fast system call entry

Linux allows direct access to system calls using the int 0x80 instruction:

section .data

; No data needed for this simple example

section .text

global _start

_start:

; syscall: sys_exit

; syscall number: 1

; parameters:

; - ebx: exit code (0 for success)

mov eax, 1 ; syscall number for sys_exit

xor ebx, ebx ; exit code 0

int 0x80 ; invoke system call

macOSX uses a different set of registers and the syscall instruction for system calls:

section .data

; No data needed for this simple example

section .text

global _start

_start:

; syscall: exit

; syscall number: 0x2000001

; parameters:

; - rdi: exit code (0 for success)

mov rax, 0x2000001 ; syscall number for exit

xor rdi, rdi ; exit code 0

syscall ; invoke system call

When reverse engineering an executable, identifying common library functions can significantly simplify the analysis by allowing you to focus on application-specific code.

Here are some resources:

While a CPU diligently follows every instruction it receives, this unwavering predictability presents a challenge for game developers. Players crave the excitement of unpredictability to make each gaming experience unique. So, how can a CPU introduce randomness into the game world?

One elegant solution involves a Random Number Generator (RNG) that relies on the timing of user input. The CPU continuously increments a counter until the player presses a button. With the timing of button presses being entirely unpredictable, the CPU uses this ever-evolving count to generate random numbers. This injects a vital element of surprise and distinctiveness into every gaming session.

This technique is frequently employed in early games, especially when other random seeds, like the current time in milliseconds, which is guaranteed to be unique but somewhat predictable, are unavailable.

We have a specific post covering exactly how emulators works including tips for writing your own emulators:

GDB is a very useful tool to debug through an application, with functionality to set breakpoints and disassemble the code, which makes it a very useful tool for basic reverse engineering.

You may already have a game or console chosen that you would like to reverse, if not we would suggest you start with either Game Boy or the Nintendo Entertainment System as there are many tools and documentation available for these platforms.

We have pages on each of the following Nintendo consoles:

We have pages on each of the following SEGA consoles:

We have pages on each of the following Sony consoles:

We have pages on each of the following Microsoft consoles along with a section of the IBM-PC:

If you have arrived at this page you may have a few questions such as why does RetroReversing.com even exist? Well, let us try to answer this question, starting with... ...

This is a Work in progress page to list interesting articles on 2D graphics techniques to create cool effects. 2D Graphics effects How Doom’s Melting Screen Works The YouTuber decino... ...

Welcome to this comprehensive tutorial on creating a LibRetro Frontend using Rust! If you’re passionate about retro gaming and interested in creating your very own emulation frontend from scratch, you’ve... ...

Step by step guide for how to create a Reversing emulator for your console of choice. Note that you may not need this guide if someone has already created a... ...

Introduction What is GDB? The GNU Debugger or GDB for short is a command line tool that allows you to disassemble and understand the code execution of a program. If... ...

Introduction Game architecture refers to the overall design and structure of a video game. It encompasses the organization and management of various components that make up a game, including the... ...

Introduction to Game Engines & Middleware Game Engines are the foundation in which games are built, they contain all the logic to be able to show graphics, play audio, compute... ...

Introduction This tutorial series will guide you through the basics of decompiling a C++ executable, from setup all the way to reversing C++ classes. The video tutorial is created by... ...

Importing a Nintendo 64 ROM Download and Install Ghidra Before following the steps on this post please make sure you have a working Ghidra environment setup. So you should be... ...

Have you ever wondered how emulators work? How would you implement an emulator? Where should you start if you are interested in emulator development? This post attempts to answer all... ...

In this tutorial from Robert Baruch on his youtube channel [], the target chip used in the video series is the Texas Instruments 74LS01 Logic gate from 1986. First step... ...

This guide is for all beginners who are interested in learning more about the technical details of their favourite consoles and games. The guide aims to be as console-agnostic as... ...

The games industry has had its fair share of cyberattacks in the past decade and one of the main targets for hackers has always been source code. This post will... ...

Reverse Engineering of commercial Games and Applications straddles a fine line of legality. Whether a Reverse Engineering project is legal or not completely depends on how it was accomplished. Conversion... ...

Memory Hacking One excellent way to get started modifying your favourite game is to use memory hacking techniques. By learning what memory locations are used for specific functions you can... ...

Introduction Game corruption has become a hot topic recently due to many you tubers playing through games that have in some way had their memory corrupted. This practise can cause... ...

This post will give a brief introduction for the tools and techniques you need to start reverse engineering and decompiling a N64 Game. Part 1 - Looking for Initial Clues... ...

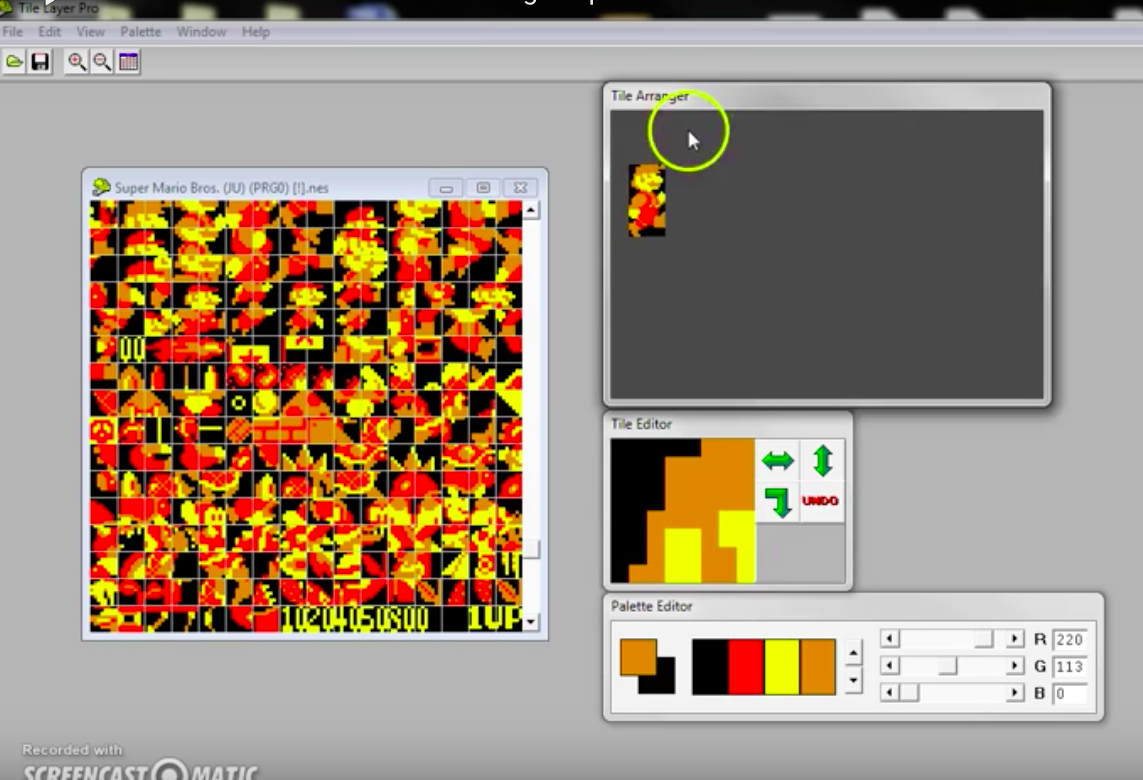

Sprite Tile editing with Tile Layer Pro If you have ever wondered how graphical rom hacks are made this is for you! This should work for most early games such... ...

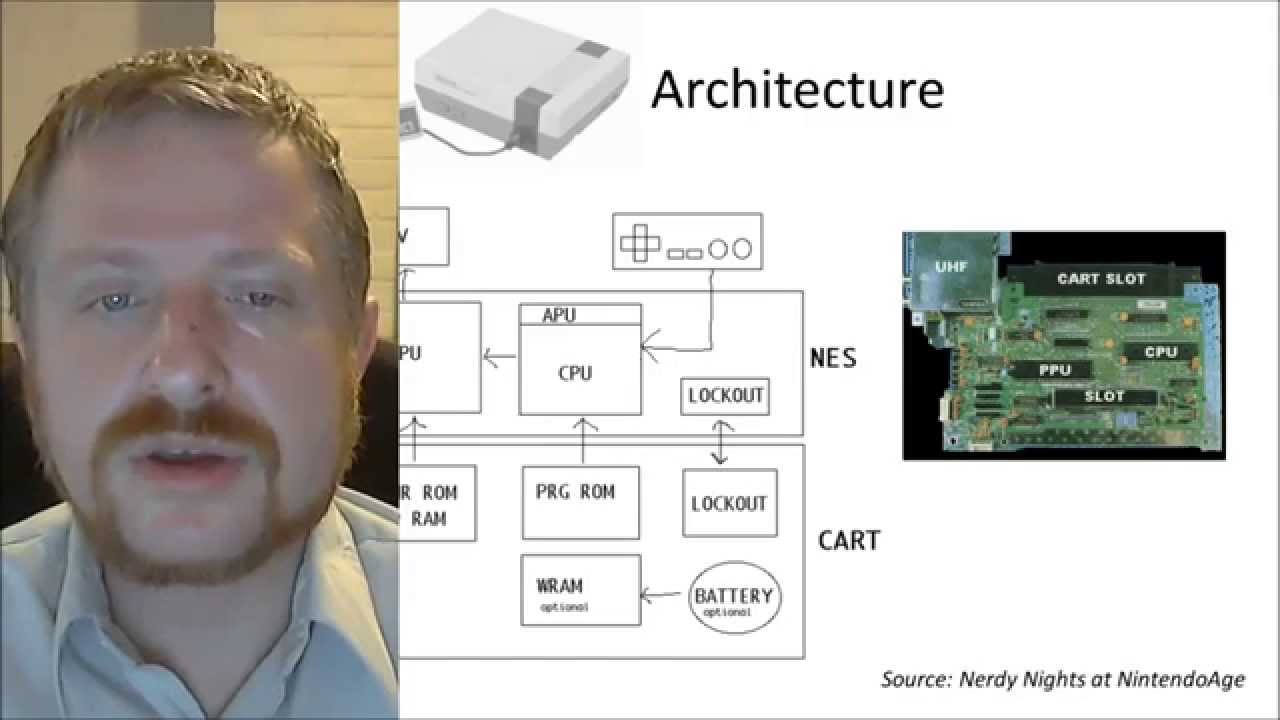

Programming the NES Dry run of the Programming the Nintendo Entertainment System talk that Levi D Smith gave at Codestock 2014 in Knoxville, Tennessee. !!Con 2017: Writing NES Games! with... ...

If you are very lucky indeed then the game you want to reverse engineer comes with full debug symbols in the form of a Program Database file or PDB for... ...

Introduction To get started the 8-bit Guy on Youtube has an excellent video covering how early computers and game consoles played sound and music 1. The gives a good overview... ...

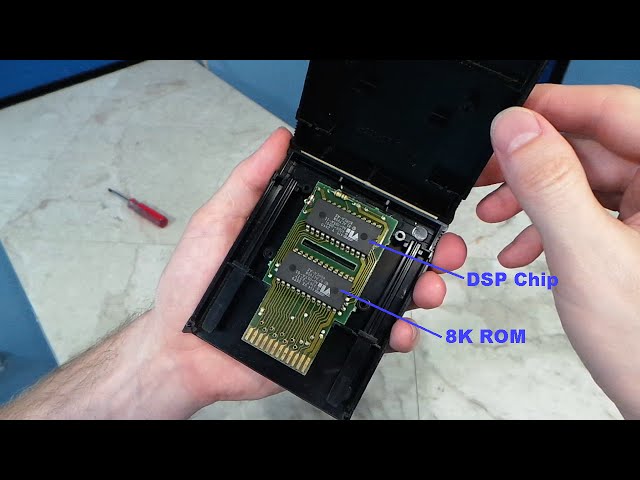

Have you ever wondered what exactly is inside those retro game Cartridges (ROMs)? In this post we will find out the purpose of ROM cartridges and how they worked. Advantages... ...

The 8-bit Guy on Youtube has an excellent series of videos covering how early computer graphics were implemented with the limitations of the hardware in mind. Memory Previously graphics chips... ...

Have you ever seen Twitch Plays Pokemon (TPP) and wondered how it actually works? How does typing comments in a twitch stream result in the player moving in the original... ...

Introduction libRetro is a versatile framework designed to facilitate the development of emulators and games through a unified interface. This post explores the internal workings of libRetro, providing insights tailored... ...

Introduction The Official Nintendo 64 software development kit (SDK) was created by a partnership between Silicon Graphics (SGI) and Nintendo to be released with the development hardware produced by SGI... ...