Unlike most PC hardware at the time the Nintendo 64 has the advantage of having its own stand alone graphics processor known as the Reality Co-Processor (RCP). This freed up the main CPU from having to do any graphics calculations and it could use all its processing power for the main game logic.

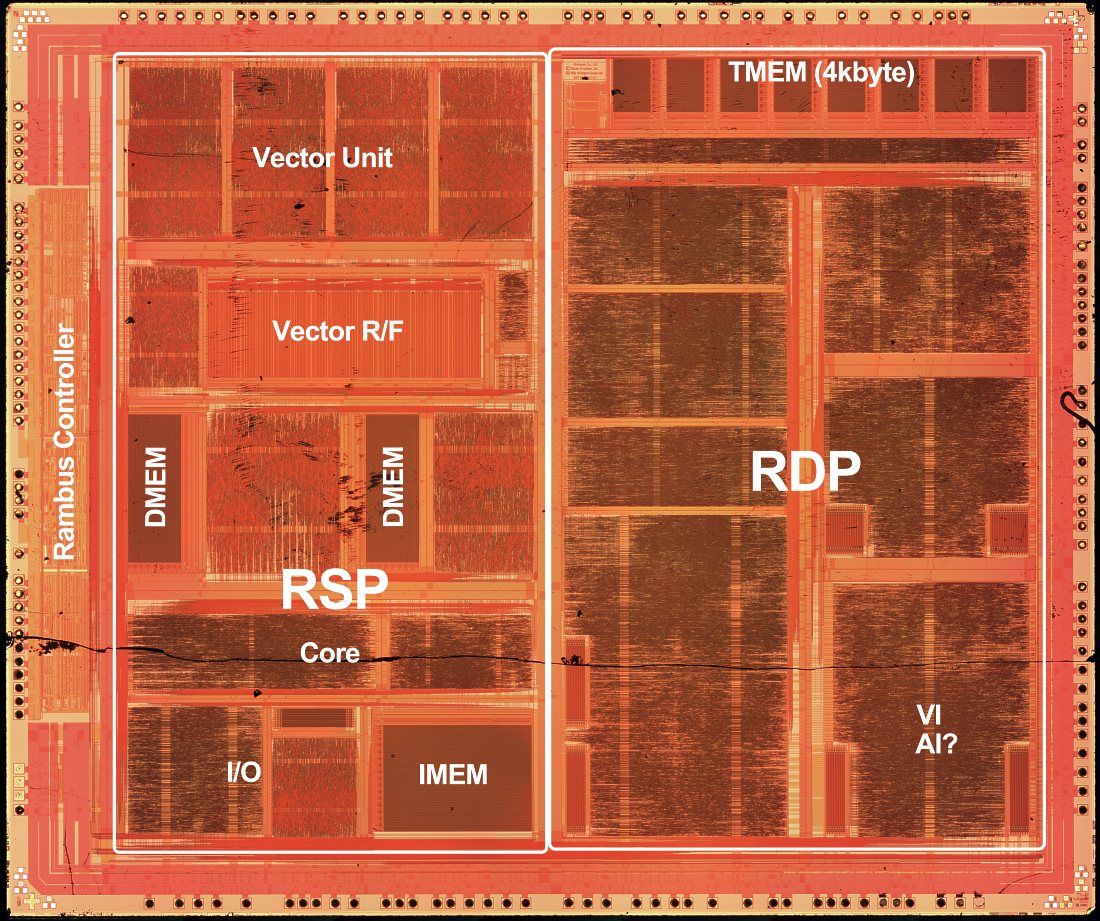

The RCP is actually split into two distinct parts one for the Geometry transformations known as the Reality Signal Processor (RSP) and the other for the Per-pixel calculations known as the Reality Display Processor (RDP).

The N64 Reality Signal Processor (RSP) is the part of the Reality Co-Processor that deals with data transform. It is a MIPS-based cpu like the main R4000 cpu but it also contains additional 8-bit vector opcodes 1.

The functionality of the RSP was first described in an interview with George Zachary in the magazine Next Generation where he described the processor as specially design for fast Matrix and addition calculations unlike the standard PC RISC and CISC based processors 2.

N64 RDP - Reality Display Processor

For more information about the second half of the RCP known as the Reality Display Processor check out this post.

You can think of the RSP as a more powerful version of the Sony Playstation’s Geometry Transformation Engine (GTE) in terms of functionality, but the RDP was a huge benefit over the Playstation as it was able to do effects such as Texture Perspective correction.

Playstation 1 Geometry Transformation Engine (GTE)

For more information about Sonys answer to the Geometry calculation problem known as the GTE check out this post.

Common tasks given to the RSP for graphical data processing are:

Common tasks given to the RSP for graphical data processing are:

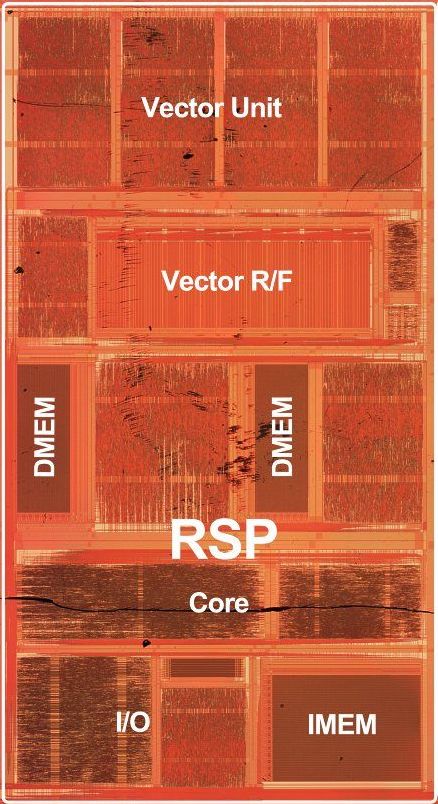

As you can see from the De-capped RSP chip there are 2 4KB memory sections inside, one labeled as IMEM and the other labeled as DMEM. IMEM is the shorthand for Instruction Memory and is just for Assembly instructions that run on the RSP, this is also known as Microcode or uCode.

DMEM is the shorthand for Data Memory and is used for all the data the RSP needs access too, so this would normally be geometry or audio data that it is performing calculations on 3.

Instruction Memory is the executable area of memory inside the RCP that runs microcode, you can sort of think of the microcode as a shader that gets executed by the RSP, however this is not quite the case.

In order to process data on the RSP the game needs to copy memory into the DMEM section of the RCP at locations 0x04000000 to 0x04000FFF, and copy the result back out into standard DRAM.

The ability to do fast Matrix and Addition calculations is crucial for 3D graphics and Audio Synthesis and decompression, so to take advantage of the specialised CPU programmers had the ability to write custom assembly for this processor known as microcode.

Microcode (otherwise known as uCode) is similar to assembly language but optimized for parallel computation of thousands of matrix calculations per second, but its much less documented than traditional assembly and took developers years to figure out how to make the best use of the chip.

Although you can initially think of the RSP microcode as similar to a modern Shader language, as they are both used to implement a programmable graphics pipeline, this is not quite the case in practise. Most of the time the developers used the Nintendo written microcode and called it as if it was a normal Fixed function pipeline.

It wasn’t common for developers to write their own microcode for their games until near the end of the N64 lifecycle. So most early games used pre-written microcode developed by SGI and Nintendo and used it like a fixed function graphical pipeline.

In fact the main reason for the lack of custom microcode development by 3rd party games is due to the poor tools and documentation provided by nintendo. Not to mention the complexity of programming for it and no debugger was provided 1.

Yoshitaka Yasumoto is credited in many games as being the microcode programmer (e.g Yoshi’s story) but most games use his microcode without explicitly giving credit as it was part of the Official N64 SDK.

If you search a N64 rom file for his name “Yoshitaka Yasumoto” you will likely find the microcode that he has written. This works for most games unless they used their own custom uCode.

The main output of the RSP microcode tends to be either graphical rasterization commands for the RDP or audio buffers for the DAC.

The list of RSP Microcodes provided by the Official Nintendo64 SDK are as follows:

Fast3D but reduced precision.Fast3D is a very common microcode provided with the N64 SDK, it went through multiple iterations during the N64 lifecycle.

It started with the standard Fast3D used in the game Super Mario 64.

It then evolved into the Extended version known as Fast3DEX used in Mario Kart 64.

Multiple versions were released of this microcode including Fast3DEX2 the second major version released and promised accelerated RSP processing speeds 4.

Later other modifications of Fast3D emerged such as F3dZEX which stands for Fast 3D Zelda Extended used in Zelda 64 5.

F3DLX (Fast3DLimitedteXture) was an optimized version of the original Fast3D by removing texture compression support, this was deprecated after version 1 and was not carried over to F3DEX2 4.

F3DLP (Fast3DLimitedPixel) was an optimized version of the original Fast3D by removing subpixel calculation support, this was deprecated after version 1 and was not carried over to F3DEX2 4.

The microcode files that have .Rej in the name subsitute the clipping process for the lighter reject processing feature.

For example this is more efficient for rendering characters as clipping is not required but would not be suitable for landscapes where clipping is required 6.

The microcode files that have .NoN in the name remove the Near Clip feature, which can be more efficient if you make sure to render your objects in the order from furthest away to closest as no clipping will take place 6.

Presumably NoN stands for No Near-Clip but this is unconfirmed.

The result of the RSP graphical calculations need to be sent to the Reality Display Processor or RDP in order to rasterize the pixels for the game. There are multiple different ways to copy the result from RSP to RDP and each provide a slightly modified version of the RSP uCode to accomplish this.

FIFO microcode uses a Queue (First in First Out) in RDRAM that is directly passed to the RDP.

The XBUS is a physical connection that connects the RSP and RDP together on the chip. This allows passing data directly from the RSP to RDP without going through any additional steps such as using RDRAM.

The DRAM method uses extensive use of RDRAM to store the RDP commands and requires work on the cpu to move the data to the RDP.

RSPBOOT is a short piece of code to initialise/boot the RSP, the assembled rspboot.o file contains in the Official Nintendo64 SDK is 740bytes but as that contains extra object data when compiled into the final rom it only takes about 208bytes (e.g Mario64).

RSPBoot is included in pretty much all N64 games and is specified in the n64 development spec file normally after the codesegment.

In an example spec file:

include "codesegment.o"

include "$(ROOT)/usr/lib/PR/rspboot.o"

The rspboot ucode is loaded into IMEM at the beginning of each OSTask (e.g in osSpTaskLoad). The rspboot microcode is used to set a few initial register values, parse the Task header and then load the next microcode.

CodeSegment.o file is generated s part of the build process for many of the demos, it can technically be called anything but most of the games call this codesegment.o. The file is a result of linking all the source files together so it is the output of the Linker (LD).

Instructions must fit in the 4KB IMEM memory region so this limits the microcode to 1,000 instructions available in memory at once (due to each instruction being 4bytes and the total IMEM is 4kb) 7.

To get around this limitation code overlays can be used and will be discussed further on, however it is important to note that the use of code overlays has a negative performance impact.

Display lists can be thought of as a set of commands that can be used by the programmer to manipulate the RSP’s currently running microcode 8. Basically we want the CPU to setup a list of commands that the RSP will use to calculate the next frame, which the RSP will run in parallel while the CPU is computing game logic.

So you can think of a display list as an array of 64-bit words (8 bytes) where each element of the array is a command that the RSP will use to render the frame.

The graphics programmer controls the RSP from main game code using the GBI.

So Display lists are created based on the commands listed in the GBI and are sent to the RSP to be interpreted by the loaded RSP Microcode.

So you could summarize that the purpose of the graphics RSP microcode is to implement the functionality required by the GBI.

https://level42.ca/projects/ultra64/Documentation/man/pro-man/pro25/index25.4.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3

https://hylianmodding.com/Thread-A-comprehensive-guide-to-F3DZEX-F3DEX2-Display-Lists ↩

https://level42.ca/projects/ultra64/Documentation/man/n64man/ucode/gspF3DLP.Rej.html ↩ ↩2

https://www.docdroid.net/NXMlF3s/grucode.pdf#page=3 ↩

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/N64_Programming/Video_coprocessor ↩